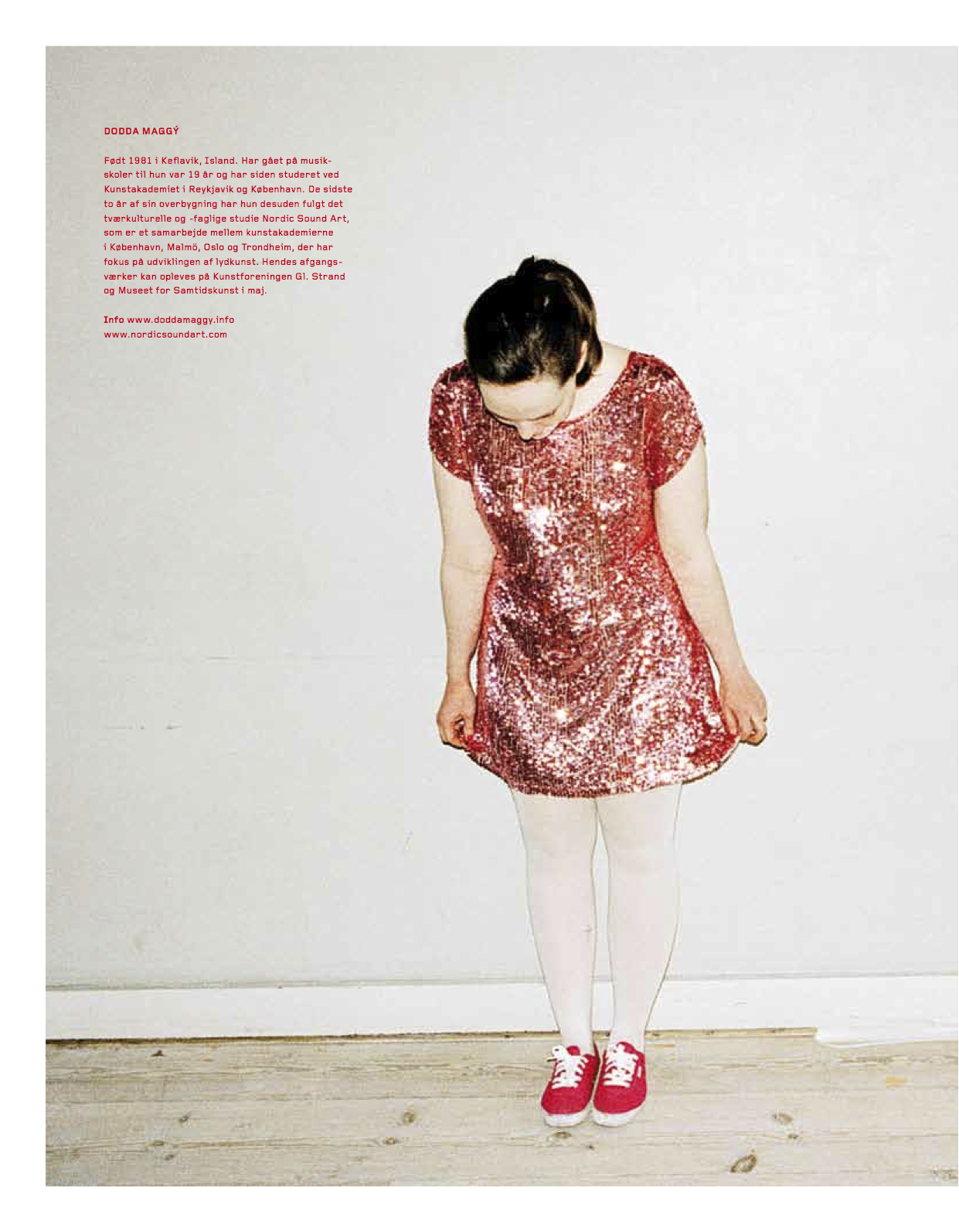

bio/statement

|

Dodda

Maggý b. 1981 is an Icelandic artist and composer based in Reykjavík.

Her practice centres around research of time-based media ranging from

formal studies of the structural relationship between the visual and

the aural to exploring the ethereal qualities of video, sound and

music. A reoccurring theme in her work is the pursuit of giving form to

perceptual experiences. Producing audio/visual installations, purely

sound based work, musical compositions or silent moving images Dodda

Maggý attempts to externalize the internal dimensions of the sensorial

and the fantastical.

Dodda Maggý holds two BA degrees from The Iceland Academy of the Arts, in Fine Arts and in Musical Composition, and an MFA from The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. She was also a participant in the Nordic Sound Art program, a two year MFA level study program in Sound Art at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Malmö Art Academy, Oslo National College of the Arts and Trondheim Academy of Fine Art. Represented by BERG Contemporary and Vane |

selected press, texts & reviews

|

Every Vibration, Every Sound, Hangs in the Air: In the

Icelandic composer and artist Dodda Maggý’s ten-minute video and sound

installation DeCore (venus) (2015), we are immersed in flickering,

undulating patterns as they build up from a single element to a cluster

of overlapping elements which looks like a parallelogram. The elements

then slowly dissolve, and new ones appear in a perpetual process of

transformation. The intricate designs, which are digitally animated,

evoke natural elements and processes such as the fractal or repetitive

patterns associated with foliage, mountains ranges, raindrops,

snowflakes or coastlines. It is evident, however, that despite the

apparent repetitiveness of, for example, a snowflake’s hexagonal

symmetry, there is a variety and depth to Maggý’s projection. Both the

images and the soundtrack consist of certain small elements which

together form and regroup into shifting entities. There is something

fragile and organic about the whole installation, as it pulses and

circulates its patterns. This flow is rendered as both audible and

visible signals, creating an ambience from these raw materials for us

to experience as part of the unfathomable mystery of life. [...] an experiential fact full of playful illusions, purposeful errors and contingent idiosyncrasies. Listening is not about the physical constitution of sound; as little as seeing is about the physical constitution of the seen, it is the perception of those physical constitutions, fraught with the uncertainty of an erroneous, unreliable ear.4

Listening is always

tinged with uncertainty and unreliability, thanks to what we cannot

hear or are afraid that we might have misheard or misunderstood. Nor

does it harbour any physical evidence, because it is always in the

process of becoming. Maggý’s work prepares for us, with these qualities

and characteristics, a new audio-visual environment, which enables us

to sink into our inner associations and memories. It even allows us to

reflect on the ways in which the human perceptual system functions as

it acts to enlighten, betray or seduce our minds. My voice defines me because it draws me into coincidence with myself, accomplishes me in a way which goes beyond mere belonging, association, or instrumental use. And yet my voice is also most essentially itself and my own in the ways in which it parts or passes from me. Nothing about me defines me so intimately as my voice, precisely because there is no other feature of my self whose nature it is thus to move from me to the world, and to move me into the world.7

Indeed, we tend to take

the voice for granted and make an issue of it only when it fails us.

Think, for example, of an opera singer whose voice suddenly disappears

during a performance or a news announcer interrupted by a coughing fit.

In Lucy, the character seems to be confronted by a voice which takes on

a character or identity of its own separately from her. In discussing

the not (yet) visualised voice in film, film theorist Michel Chion (and

Pierre Schaeffer before him) relies upon the term acousmêtre – that is,

a voice which is able to ‘be everywhere, to see all, to know all, and

to have complete power’.8 He also connects the power of voice to

a form of panoptic fantasy, or total mastery of space through vision

and concludes that the intervention of an acousmatic voice, or a voice

heard in the absence of a physical body visible on screen, often makes

the story into a quest of anchoring this voice there. |

|

ARoS FOCUS // NEW NORDIC: The Sound and Video Works of Dodda Maggý LP Where do you find inspiration for your works? DM

Yes, it really is. In my recent works, I’m working much more formally

with these animations and, in a way, I’m exploring compo- sition and

music visually. But I’m still composing when I create images; they’re

made with a musical sensibility. And, actually, in some of my older

works, I was using music as a narrative tool to drive the underlying

‘story’ of the piece, as the music was paired with video. I’m composing

a visual language of music appealing to all senses, somehow. LP

So when you say that you’re also very inspired by films, how does that

relationship work, then? Is it from well known classical films or is it

more from film theory that you get your inspiration? DM

I use a lot of technical elements from film theory in the way I work

with video. There are some technical devices in the cinema that are

quite underestimated. Like the power of audio. We sort of forget about

it, we forget about the sound design, and we forget about the music;

we take it for granted that the sound is just a natural component of

the image when, in fact, it’s constructed and added after filming. If

you remove the music and sound de- sign, the film would collapse. As a viewer,

you become familiar with the language of moving images through popular

media. For example, it wasn’t until I was in art school that I really

started to study video art and, even at that time, in the early days of

YouTube, you could only see video art in museums and galleries. I could

only read descriptions and see stills of a lot of the pieces that I was

learning about. Today, you can find almost anything online. So I use

these structural devices that viewers understand to create my work, but

I don’t necessarily use them conventionally. I’m not a tradition- al

filmmaker. I play with the devices, sometimes skewing and twisting them. LP So, it’s more on a technical level than on a story line level? DM

Well, I think it’s both. I think that a significant part of the story

is portrayed through sound. It’s just not always obvious to the viewer.

Through sound, the viewer experiences another level of the narrative,

and the sound contributes a lot when creating the energy of a film. I’d

say that we, as viewers, underestimate the power of sound design. My

earliest influence was David Lynch and particularly the old Twin Peaks

series. I’d go so far as to say that a lot of his work really is the

sound design, the way he uses music. The sound is really what creates

the energy in his visuals. For example, he sometimes uses a very low

bass, almost so low that you cannot hear it, but it moves the air, it

sort of creates another dimension of something you can’t see, which, I

think, is a theme he often works with. LP

I recently heard a documentary about how David Lynch collaborated with

the composer on creating the theme tune for Twin Peaks. How they did it

as a mix of everyday recognisable sounds, which fill our daily lives

without us noticing it, but still carry a huge part of the meaning. DM

Yeah, totally. Even in the new series, I really do think that David

Lynch is very much working like a sound artist. David Lynch and Angelo

Badalenti used the music technique called

leitmotif, which comes from opera (Wagner) and denotes a short, musical

phrase associated with a particular person, place, or idea. Now it’s

standard use in the cinema. But in the old Twin Peaks, Lynch gave each

individual main character their own theme song and he then wove these

themes, these leitmotifs, together with the overall music. He used

leitmotifs to indicate something that’s happening ‘below the surface’.

For example, when we hear a theme of a character not appearing on the

screen, the viewer can’t see him, but his presence is looming. LP

Let’s move on to your kaleidoscopic works. In some of your works, the

symmetrical visual patterns are constantly transforming into

‘kaleidoscopic’ compositions. What do you intend to show your audience

by using this approach? DM

Well, I’d like to start with the first one I did entitled DeCore

(aurae). That piece represents a new way of working. I was really

interested in sound art – I feel that I’m always working with music

even if it’s in videos. It started with me filming plants and then I

began manipulating and sampling the images into new organic shapes and

putting these back together in a new structure. It took me four years

to work out this piece, since it was so tricky to turn it into

something interesting. There’s a fine line when working with something

that you want the eye to engage with, something that could be viewed as

merely decorative. It’s really tricky because it’s so easy to label it

decorative and thus redundant. I’m playing with this line and poking

fun at it, hence the title DeCore, a play of words for something that’s

perhaps decorative and something that’s hard core. I’m pushing this

idea of constant rapid movement; the eye is almost always unable to

catch the image as it is forever changing. What I found

was that proportions are the key. They are the key elements in our

experience of something as being visually pleasing or displeasing. With

DeCore (aurae), I’m transferring the way I work with sound art and

field recordings into visuals. I’m recording images and

sampling/manipulating/changing the recordings and layering them whilst

creating new structures. When I did this piece, I was thinking of

music. I really approached it as if I were making a sound piece – even

if it was silent. I was working with the proportions of the shapes in

the image, structuring them proportionally as you do when composing

notes; creating intervals which are basically just notes structured in

certain proportions. I’m making harmonies, structuring the rhythm of

the movement and creating colour combinations. But there’s another

level, too; usually when I am working, there’s a personal approach and

a formal approach. So you can often enter my work from different

perspectives. In this instance, the personal connection to the visuals

that I started creating really resembles an experience of migraine

where I lose my sight. I gradually go completely blind and, as I lose

my normal sight, I start to see these colourful organic shapes. A lot

of people experience this and it’s called an aura. Each individual

experiences it differently but, in my case, it’s like these flashes of

lights and colours and shapes that sort of take over my field of vision. LP Like looking through a prism?

DM Yeah. Exactly. But it’s never the same shape; the shape of the image or the hallucination changes each time. LP Could you please try and explain to me how, technically, you compose the visuals? DM

Like with DeCore (aurae), it starts with recordings of plants and

flowers. Then I take this material and I manipulate the images with

filters and effects to create new organic shapes. And then I do it

again, and again, and again. This is often how I work. It goes through

many different stages of change until I achieve the final shapes. I

actually created, like, two hundred new visual flowers that I then used

as a base to create new shapes by layering them into new combinations.

In DeCore (aurae), you can see the visual flowers as both really big

and really small. I manipulated the video so many times, layering it,

that I was able create the final structure from a sort of patchwork of

video fragments. LP

So you create this composition as you would a piece of music and then

there’s a personal level that refers to a health condition that you

have: the migraines. The formal element that you mentioned is the rules

or the rhythm that you’re incorporating into the repetitions, so to

speak? DM

So there’s a structure of forms and colours, of movement and rhythm.

There are different things and ideas behind it. One is that I formalise

the structure of the visuals in the way I would compose sound on a

timeline. For example, the structure of elements moving in a repetitive

motion is the same that I might use when constructing a sequence of

musical themes or melodies in a musical composition. Another is that,

with the continual rapid movement, my idea was to represent the idea of

‘energy’, something that’s never still, constantly moving and changing.

Also, the movement is reminiscent of the way I experience the visuals

in the migraine hallucinations, the shapes flashing and moving. LP Yes, but the rhythm is also in the repetition of the gesture that you copy over and over again? DM Totally. And that’s actually sort of a recurring theme for me, this repetition of patterns. LP

So when you’re fascinated by something that looks like a kaleidoscope,

does that refer to your migraines or does that fascination stem from

somewhere else? DM DeCore (aurae) comes from these kinds of hallucinations or what you’d call it. That sort of led me on to exploring geometry and sacred geometry that goes even further, to these alchemist graphs where you have forms or shapes which, when puzzled together, all fit into different combinations. Sacred geometry led me to explore alchemist graphs, which go into a sort of mystical space. The graphs are used as symbols for hidden knowledge in the occult or mystical groups and my fascination with hallucinations comes from the shapes I see, these fractured shapes which are somehow everywhere in nature. This fascination led me on to exploring fractals and from there on to geometry. In DeCore

(rosen), which is the silver piece, I’m really exploring sacred

geometry and the main visual motif is actually created from an

alchemist graph. This is the first piece that I created from something

else that is not conceived within my own self, but from an image that I

found. I’ve actually been collecting images of alchemist graphs for a

long time. I didn’t really want to, you know, understand them or try to

find a meaning in them, but I still wanted to access them and make them

my own. I wanted to absorb the images and then create my own output

from those images – and in that way try to understand them. Not by

reading exactly what it was supposed to mean, but by assimilating it

into my own work. My own process of working with this material. LP And in what way does Curlicue (spectra) relate to DeCore (aurae) and DeCore (rosen)? DM

They all connect. They all sort of paddle along some road that I’m

exploring. In DeCore (aurae), I’m working with these images of plants

which exist in the real world. In both DeCore (rosen) and in the

Curlicue (spectra), I’m working with an idea of artificial material,

material that doesn’t exist in the real world. While in DeCore (aurae),

the base material is images of plants, the base material in DeCore

(venus) are pearls. In DeCore (rosen) and Curlicue (spectra), the base

material is created in a 3D software where I created 3D circular shapes

that I used as the material for new constructed shapes used in a more

traditional animation technique developed by myself. So the source

material is computer-generated, one might call it a non-existing

material, but the way I work with it is by using an animation

technique. As in the other works, the images and shapes are created

through multiple processes. Curlicue

(spectra) is a reference to the migraine hallucinations. This is, so

far, my closest attempt at portraying these hallucinations. They are so

colourful, almost like bright neon lights. Like if you compare it to

the resolution in a video, it’s like 1000K. The resolution is so fine

that it’s utterly impossible to portray. Last time I had one I was

thinking, “Okay, I’m going to grab a pen and paper and I’m going to

draw it.” But when I was actually about to do it, I looked at my pencil

and it was like I was drawing with a crayon compared to what I was

seeing. It was just impossible to try to capture the colours and the

speed of it – as it moves very quickly – it’s almost neurological. It’s

very colourful, the whole colour spectrum. There’s also a meditative

element to Curlicue (spectra), both in the image and visually. The

spiral grows continuously but still contains its shape. There’s

movement but still nothing changes. It’s slightly similar to Minerva in

terms of dealing with ideas of time and space. I think we

all have an internal visual world that it would be fascinating to shape

out in materials, so that we could see each other’s inner visions,

which is what I’m really fascinated with. I actually very rarely talk

about these hallucinations, because it’s so personal and somehow it’s

easier to talk about the formal aspect. LP

I would like to ask you about the women in your films. They look like

archetypes in Hollywood productions and you’ve chosen to work with a

certain kind of female figure in your films. Could you tell me more

about the kind of woman or kind of female figure that appears in your

films? For instance, what fascinates you with the crying woman in

Madeleine? DM

That’s a very direct Hollywood reference. In Madeleine, I was re- ally,

as a performer, taking on the role of the actress. The idea comes from

a split desire within myself – as with everybody – to be desired. Women

have been portrayed in certain ways in the media and we have an idea of

what it is to be desirable. And this stereotype of the desirable woman

is something I both want to embody, but it’s also a stereotype that I

despise and want to reject. And I despise this desire in myself. As a

performer, I’m confronted with this issue and I’m often dealing with my

own desire of wanting to be presented in a certain way. So, in

Madeleine the character is quite ironic, I think. She is glitzed up

with the lights, this Hollywood lighting, and make-up, and this pink

glittering dress, and then she’s crying. It’s almost like a fetishist

kind of crying. It’s almost like she’s enjoying it. LP Fetishist crying, you call it? DM

Yeah, you know. It’s so over-sentimental that, to me, it’s totally

ironic. It’s a character that we know, especially in old Hollywood

films – the helpless woman that needs to be rescued. For example,

in the film Notorious by Hitchcock, Ingrid Berg- man starts out as this

strong rebellious female character hunted by the secret service, and

then at the end of the movie, she’s giving away all her power and needs

to be saved by the male hero. This is the scene where she’s the most

beautiful and one experiences the ending as romantic, it’s like the

perfect movie ending. It’s quite disturbing to me that we’re so used to

these female characters. LP Does that relate to the female person in Lucy, too? DM

Lucy is a bit different, actually. But they’re still connected, because

in there I’m portraying an opera singer. In Madeleine, I’m taking

on the role as an actress and, in Lucy, I’m taking on the role as opera

singer. In both, there’s this very embarrassing desire that I want to

be the actress, and that I want to be the opera singer. It’s really

role-play, and it almost goes back to this sort of playing, you know,

when you were a kid taking on all these roles. Well, I was just sort of

role-playing in my studio, and I just thought, “Okay, I’m not an opera

singer. But I want to be an opera singer, so I’m going to make it

happen. I’m going to create the space for myself. I’m going to create

this world. Nobody else is going to hire me as an opera singer.” LP But what’s this fascination with opera singers about? DM

I’m really fascinated with tragic heroines and Maria Callas,

especially. She’s such an extremely tragic figure. I’m fascinated with

these really strong females, like Maria Callas and Jacqueline du Pré,

the cellist. I can’t really say why, but I’m just sort of fascinated.

Actually, I love Maria Callas so there’s a basic desire in me; I want

to put myself in the shoes of Maria Callas and, at the same time as I

did that piece, I was really exploring the voice as a phenomenon. And now it

goes into film theory; in the cinema, the voice is often used as a

character. Especially when it’s a voice that doesn’t have a body, like

a narrator, or you hear a voice, but you never see the person. This

sort of voice almost becomes supernatural. It has the same qualities as

a being that is otherworldly, because it doesn’t have a body. It comes

from a writer called Michel Chion. He’s one of my favourite writers. He

has a name for this bodyless voice. He calls it the acousmêtre. It’s

French and doesn’t translate. LP What does it mean? DM

The word comes from acousmatic and it actually goes way back to

Pythagoras, who used to teach his pupils behind a curtain. So his

pupils weren’t allowed to speak, and he used to stand behind the

curtain and teach, so that they wouldn’t see him. They could only hear

his voice. So it refers to this ancient way of teaching. The followers

of Pythagoras were called acousmatics and this bodyless voice is called

the acousmêtre. I was really exploring the voice and, at the same time,

I created a musical composition. I was working with the voice as a

material and as this ‘semi’ being’. When I was developing the piece, I

really had to find this voice. The way I’m singing in Lucy is not my

usual voice. It was, like, a voice that I had to find or create within

myself. I had to look for it and I found this voice within my body, an

entity that wasn’t really mine. I’m focusing on the voice as a

material; so when I recorded the voice, I did it in close to try and

find the grain – the physicality. The physicality is sort of the

structure. And then the way that I composed the piece in terms of

chords, the way I layered the voices together, I was really trying to

create a feeling of light. I don’t know if it makes sense? When I was

composing it, the chords and the sonic affect, that I was trying to

portray, was light. It’s mastered in surround sound. It’s the

experience of a voice floating in space. It’s the voice, it’s like this

bodyless entity that moves around the speakers and, as a viewer in

space, you’ll feel the voice flying around you. The story of

the opera is really about this character that has a voice, a voice that

seems to be always escaping from the character – or possibly

embodying the character. And we can only see the character when the

voice, the sound source, is actually coming from the image. It can feel

as if you can only see the character when the voice is where the body

is, and then it escapes. It’s the drama about this character trying

to embody and hold on to this voice. But it’s all disappearing in

darkness somehow. LP

Now we’ve been talking a lot about sound and the underestimation of

sound in visuals, but you have a film in the exhibition that is

soundless, Minerva. Could you please tell me a bit about it and why

it’s without sound? DM

I think that silence is as important as sound. I also use silence as a

device. I never put sound to an image ‘just because’. Or an image to

sound ‘just because’. There always has to be a reason. So if there

wasn’t like a purpose for it, then I would rather have it silent – or

the other way around. LP So why is it silent with the owl in Minerva? DM

First of all, I don’t think that sound adds anything to it. But the

thing about Minerva is that there’s this owl that’s sort of continually

flying, but it’s not going anywhere. It’s in this sort of dark space.

Or not even space. It’s out of time and out of space. There’s no sound.

It’s this other dimension which is outside of out of time and out of

space. Minerva is really about time and space. Or the absence of time

and space. The way I approached Minerva, actually, is how I would

approach drawing. LP How is that? DM

Often when you draw, it comes straight as an idea and you draw it down.

The drawing is a bit more spontaneous. I think it took me 2-3 months to

create Minerva, working day and night, which is like the fastest piece

I’ve ever done. Timewise, if you compare, like, a drawing with a

painting, to me, Minerva is like a drawing, even though it took, like,

2-3 months. Like a quick sketch. |

|

Variations at BERG Contemporary Dodda Maggý is an Icelandic artist and composer who employs the methodologies of musical composition and filmmaking within her unique work that is strongly influenced by a cross-disciplinary approach. It is difficult to affix her work within one field or artistic genre. It can best be described as lingering on the verge of cinema, sound art, video art, and music composition, belonging in between them all. In addition to her visual arts background, she has studied music and cinema. She carries a strong passion for narrative cinema and experimental documentary filmmaking into her artworks that bear strong references to both disciplines. Dodda Maggý’s work emerges from the observation of the relationship between an internal and an external image. The artist analyzes the development of internal images that are born from personal dreams and imagination, putting those experiences forth as the fundamental basis of the work. Dreams, fantasies, and memories become the core subject matter of an audiovisual composition that gives the audience the possibility of becoming part of new perceptual experiences. Exploiting the potential of digital technology, Dodda Maggý divides the image into different elements, each encompassing a specific structure. As within a soundscape, the motion of each element creates a self-organized organism. This is a structure we would find in a cultural context, such as music, as well as in nature, such as the growth of a human being’s mental images or the developmental processes of plants. It is therefore safe to state that the connection between cultural and natural processes is important in Dodda Maggý’s work. The artist’s work develops a new way of understanding mental and physical evolutionary phenomena through a visual music narration. The notion of narrative is important for understanding Dodda Maggý’s work. If we look at the videos in this exhibition we don’t see a conventional cinema-like example of narration or a linear story, but an unorthodox unveiling of an evolving process, a playful constellation of creative elements. The formalistic narrative work that bears striking methodological evidence of musical and cinematic influences is evident in Étude Op. 88, No. 1, one of the three main pieces in the exhibition. The work is composed of 88 opal stones, each stone representing a note of a piano, creating a direct correlation between the image and the sound of the stones. The work encompasses seven prints materializing possible harmonic combinations. The structure of Étude is based on a concept of “visual music” that harks back to the 1910s and ‘20s, inspired by the John Whitney method of composing, creating musical compositions with visual imagery. Dodda Maggý’s formalistic approach to image and sound is evident in her work entitled C Series, this time using video as a tool to compose music. The series relates to Étude in that it examines a single instrument, in this instance the flute, choosing fifteen notes from the instruments range that correspond to fifteen circular images that are animated into fifteen video loops, where each form represents a note and the forms create a complex visual layout. The sound is made to stand independently, with the video removed. This is the foundation for further musical composition within the piece, starting through the process of structured visuals, sourced from the carefully chosen initial fifteen notes. When the musical composition was complete she created a new video animation, titled Coil (C series). It is made from the same source material as the 15 animated forms, but presented in a new structure that is intended as a visual focus point accompanying the sound. It was later also detached from the audio as the working process progressed. The videos are therefore evidence of an artistic process—not a direct visualization of the sound heard in real time, but simply a material suggestion of what sounds might look like. Each note is presented in a wide range of tuning, interacting with one another in endless ways, each revealing the many temporal layers of the artwork’s creation. Dodda Maggý focuses on the relationship between mental and actual phenomena. Transforming mental images into audiovisual ones, the work of the artist produces the perceptual experience of the audience. In that way, the exhibition space becomes an organism in which the audience faces new cognitive realities. Such is the case in DeCore, a series started in 2008 that reflects on mental phenomena such as hallucination and synaesthesia, as well as concrete objects. The artist creates new organic forms by recording flowering plants, applying recording and the methods of sound design to video. The flowers are detached from the background and resampled. The concrete objects in this case are the flowering plants: phenomena in motion. The work is an ongoing organism composed of many different little elements (or frames). Every single frame is in constant motion creating a fractal structure. The exhibition is therefore composed of three main pieces, not conceived separately and, just as in Dodda Maggý’s artworks, the exhibition combines different self-contained elements. All together these elements create a complex organism that can be perceived from different points of view. The three pieces are designed to allow the audience to move freely in the exhibition space, to navigate within a myriad of cognitive possibilities, without any obligation to follow a fixed trajectory. |

|

Variations by Dodda Maggý at BERG Contemporary Erin: Can you tell me about this piece (DeCore (etude))? Dodda:

So this is an ongoing series called DeCore that started in 2008. When

it started as a video I was working with methods of applying field

recordings and sounds to video. I basically went around with my video

camera and filmed flowering plants and trees and then started to

manipulate that material to create new organic forms. The first

version, which was called DeCore (aurae), took me three years to figure

out the right form. I was thinking a lot about visual music as well as

synesthesia, the state of having your senses crossed that causes people

to see music or experience forms as colors. I was applying these

methods and sounds to video and also thinking about how to represent

music. DeCore was then installed as a large silent installation,

followed by another version, and now I’m showing two of the newest

versions here, DeCore (etude), and DeCore (loom). It’s the same source

material of trees and flowering plants, actually. I’m continuing to resample in this

exhibition. However, I’m not re-sampling the works themselves but going

back into the source material and making new manipulations- almost a

remix of the original recordings. With this piece, I actually wanted to

take the source material and create print stills. It’s another thing to

really create the image rather than take a still, so I created the

video in order to take the still image. Erin: It’s going from 3D to 2D, so of course, it’s a huge recalibration. Dodda:

You have to think about it differently. So this is like the DeCore

series but evolved. I’m still thinking about music here and I think

music is still the understory of everything I do. I start with music

before visual arts. Erin: You studied both right visual art and composition, right? Dodda:

I studied both. Before I went to university I felt like I had to make a

decision between going further into music or visual art and I chose

visual art because I felt there was space for both. Later, I finished

studies in composition as well. I think as a visual artist, I really

connected with video and this time-based medium because I understand it

as it relates to music. Erin:

It’s as though your process of making videos is an image of harmonics

itself, so your work is both in the medium and the resulting image. Dodda:

That’s my aim, but we can debate whether it comes forth. In this piece

with these small sorts of flowers, each flower is made out of many

recordings of flowers, so there are many details combined. In just one

little flower there are multiple processes happening at once. I like

the size of it because you can see the details. Erin:

You’re making your own language, it seems, by working with each note in

itself and making them work together to become its own vocabulary. What

programs are you using? Dodda:

I use a lot of programs of all kinds and am mixing all of them. It’s my

own method of layering that I developed with many variations. Erin:

The last exhibition here at BERG was of Steina and Woody Vasulka, the

video art pioneers. They were some of the first to make tools that

would manipulate audio into visual and vice versa. Dodda:

There is definitely this link. Steina actually was also trained as a

violinist first. Having a background in music seems to be the case with

a lot of video artists, especially in Iceland. Erin: Narrative and rhythm seem to be two intertwining themes in the exhibition, each carrying the other forward. Dodda:

That is definitely the case with the videos, especially this one that

I’m making to create prints from. I’m making the videos with this

musical application and thinking about proportions. Just like with

different chord combinations and sounds that make major and minor

chords, we also have these proportions visually which create tension or

harmony in the image so there is also geometry involved. I’m applying a

set of movements to this, as well as colors obviously. This is much

more monotone, I would say, but maybe baroque monotone. The first

DeCore had each frame changing and was more chaotic but this is more

still. It holds the shape but it still changes in color. This looks a

lot like rhythms, almost like beats. Erin:

I was reading another an early article about your work about how your

work engages the viewer visually but the rhythm engages your body, so

it somehow traps you between these two states of being when you’re

watching it. Perhaps this was more the DeCore installation when the

viewer could be part of the projection and be very physical, but I

think it still has a very mesmerizing effect on both body and mind. Dodda:

I’m very interested in these sensorial effects. My earlier work was

more portraying these different states while now I’m more interested in

creating this effect for the viewer. I know I can never estimate how

the effect will be on the viewer, but I can stimulate some senses,

definitely. Erin: Where does the name DeCore come from? Dodda:

DeCore comes from something on the verge of being decorative, which is

a total taboo. When I starting working on DeCore in 2008, to do

something decorative or visually appealing was almost like porn. So I’m

playing with crossing that line and questioning if it being visually

appealing makes it less interesting. I’m playing with these aesthetics

about how the proportions and harmonies bring affects. It’s also on a

fine line to do something flowery so there is also a play on that.

There is so much information in each frame, really, so I’m just pumping

information out. Erin: Isn’t it like that with music? Why is music allowed to be harmonious but not visual art? Dodda:

It goes in circles. After the Second World War, Romantic music was just

not allowed. So, really serious, atonal music came into fashion because

this Romantic music was connected to nationalism and it was totally

out. It really just goes in circles depending on what is accepted at

the time, beautiful music or atonal music. I think there’s been a shift

in the last ten years, although it’s almost hard to say this out loud.

I feel a shift from a focus on very theoretical to a slightly more

Romantic, or more spiritual aesthetic. I think the themes I have been

flirting with are actually being more accepted whereas before they were

a little bit ‘outsider’. Erin: I think it is definitely a noticeable shift. Dodda:

I don’t know if it is a trend, but it is definitely more accepted. Even

before, to talk about energy, was a bit out there. It wasn’t really

what my teachers were going for when I was in school, either. I can’t

generalize it but I can definitely feel a shift in the atmosphere of

what is going on and what is accepted. Erin: The new age needs a new age, it seems. Is all of the work in the exhibition a variation of DeCore? Dodda:

No, there are three variations. We have three main pieces: DeCore, C

Series, and Étude. Moving from DeCore to C Series, I am really

continuing to investigate this relationship between the visual and the

aural. I was interested in making a technique of composing using video

and music but here I am much more in composition mode. I’m studying the

flute as an instrument. I picked fifteen notes to work with and

composed them in this one composition that is part of the exhibition, a

nearly 18-minute long piece. I made these video forms, a circular

form with different proportions, for each of the 15 musical notes.

Then, I connected each note to this form and I created a video

animation with the music corresponding to what is happening in the

video. With each composition, I pair a note to a form, which creates

the musical composition. Later, I decided to remove the video and

compose on the base of sound. I have one video from this process, but

I’m only going to show the notes. When I was making the composition, I

made another video from the same source material which became Coil, a

part of C Series. C Series is the focal point for the

composition and so the accompaniment for the music, but then in the

working process, I realized I didn’t need it. I’m just showing the

music, like a work in progress, that shows how I composed this piece.

If we go into the purely musical side of it, it appears as though I’m

working in music. However, I’m not that interested in just composing.

I’m interested in detuning. We have this modern way of tuning

instruments at 440 hertz. All instruments are tuned after that, but

there is an older tuning at 432 hertz. When we tune after that the

harmonics are a little more balanced. There are a lot of different

theories about why we changed it, mostly conspiracy theories, but no

one is really sure. So the tuning today is a little bit harder. You can

see in visuals of chords how the frequencies make different forms. I was thinking about how interesting

this conflict is and wanted to start to detune my notes. I’m working

from the range of 440 down to 432 up to 448 hertz so my instrument is

mistuned. What happens when you have these fine misattunements is you

get these frequencies that meet and give off all these vibrations,

overtones, and new frequencies that erupt. Even if it is fifty notes,

and three octaves, they are all in a different tuning and when they

meet they create this friction. I also took the notes I created and

manipulated into each of these movable forms. I changed the speed of

the vibration, so it was shaped by how quickly the note reverberated. As you can see, I’m really going into

the material and treating musical notes as material. Each note is

carefully created and then manipulated. Afterwards, I layer them and

compose them together. You can hear this piece on the record and you

can also see these two projections in these two projections on the

wall. They are still part of the piece and part of them will be in the

daylight, so they kind of disappear into the light in a mystical way. Erin: Can you explain this visual (the animated projection in C Series) a bit and how it correlates to your vertical investigations? Dodda:

So the music is a vertical investigation and that’s the translation

from lyrical film where I’ve been working in video with this vertical

investigation with video that I’ve been applying to music as well. This

piece is the one I made after the composition was finished and is

actually a result from starting DeCore and investigating proportions,

going into geometry, and alchemist’s graphs. This is actually created

from an alchemist’s graph and shows an Egyptian energy key. I don’t

make my work after other images, though, I have three works where I’m

working with alchemists’ graphs. Usually, I never use outside material

but I was just interested in these geometric images that have this

visual energy to them. There is some message being told and I’m not

exactly interested in finding out what it is supposed to tell me but

I’m interested in the energy of them. That is why I wanted to

assimilate it into my own process. Erin:

The name of it even, ‘alchemist’s graph’, sounds like a parallel

investigation to the work you’re doing. What an alchemist does is tries

to transmute gold out of these chemical elements. Dodda:

But it’s all symbolic in the end. When they’re talking about gold

they’re actually trying to find spiritual gold. It’s spiritual, not

material. Alchemist’s search for gold was sacred knowledge. Erin: Even that transition between material and spiritual knowledge and matter is like a parallel investigation to what you’re doing. Dodda:

Especially in this one because I’m working with the base material in C

Series which is actually these 3D computer generated spheres. I

basically took snapshots of 3d images and took them through a very 2d

way of working, almost to this old school level of animation. So I’m

working with this artificial form to create this alchemist’s key. To

me, it feels like energy plugged into this loop. It also reminds me of

the music symbol where you have an F key or G key and you ascribe a key

to your composition. I’m also breaking a lot of musicology

rules here by playing with terminology and using it inaccurately on

purpose. The tradition is such a long one and can be quite fixed, so it

is perhaps good to playfully skew it a little. I also did this with

Études by really playing with the terminology. We’ll be releasing a

record on the opening, a limited edition vinyl of 30 editions that will

also be on Spotify. I’ve been working with music for such a long time

and it has been such a nice experience, materializing these prints, so

releasing the prints and materials and music as materials is quite

exciting. Erin: You’re working in such an immaterial realm, so I can imagine it is exciting to have such a material outcome in an exhibition. Dodda:

It’s a new development in my work for sure. Here are the different

forms of the notes for C Series, screened as just a small projection in

the exhibition. I find the musical compositions much more interesting

than the visuals actually. The original animation I made doesn’t add

anything to the composition so when I’m working with video and music

together there always has to be a purpose. If there is no reason I

usually take it out as I would rather have silent videos or stand alone

sound pieces. You can see this is just how a material note might

materialize. I’m just opening up ideas of what music might be. This

almost could be presented as a sound piece as I’m working with sound

ideas even though it is silent. Erin:

This is a similar shape to the Mandelbrot set, a fractal named after

the mathematician. Anytime you zoom in or out into one specific part

you come out eventually into the same shape for infinity. Dodda:

You can find it in nature and in the cosmos. The environment is just

the basic building block of everything around this fractal

relationship. Even in these snapshots of planets of stars, it’s always

fractals. Even the path Venus moves around the sun is a fractal. It

makes one wonder how everything is connected to these forms. Erin:

You can look at your work very formally. You don’t have to go there,

but it’s laid out for you if you want to, however you can also just

recognize the mathematical and musical harmony in the formalities. Dodda:

If people are interested in certain subject matters they pick it up or

they don’t. There are different perspectives of looking at my work-

very formal, very sensorial, and sometimes working with more mystical

ideas. I’m always questioning and never offering answers. Erin: You’re still very technical in your mystical notions, which is a beautiful combination. Dodda:

The last part of the exhibition is called Étude for which the basic

building blocks are these Opal forms. There are different

investigations into visual music which started in the 1910s and 20s by

visual artists trying to find ways of composing music visually. It’s

hard to define as a genre because it crosses all these styles between

animation and structural film, but the umbrella term is ‘visual music’

which began in Europe and was developed later in California. One

experimental filmmaker, in particular, was intriguing for me, John

Whitney. He regarded himself as a composer but his instrument was the

camera. He spent his career trying to develop ways of translating

visuals into music. So I was quite inspired by his technique and wanted

to experiment with his technique to apply it to my own experimentation.

So I’m not duplicating but I am interested in how he structures

entities together in a visual. I think there is definitely a visual

reference to his work in Étude. Étude pays a little bit of an homage to

him in the name Étude, which is usually a musical composition that a

skilled composer creates for his student to practice. I’m using it as

an exercise for practicing visual music. I want to make a visual music piece in

this tradition and so I regard this as my practice piece in visual

music with a certain methodology. I’m also making a wordplay between

the use of “Opus” in music which stands for the “work number” and is

written as Op. In Étude, Op. stands for the number of opal stones, so

the first piece is actually 88 Op. I’m also examining the piano in

particular by working with 88 stones which represent the 88 notes of

the piano. In the Étude series of prints, you can

see the full 88 notes, as well as compositions with 22, 33, 44, 55, 66,

and 77. So I’m making up these rules, imagining how to materialize

chords into a visual. I created these seven structures that are in the

composition and I these as my elements in the installation. So this is

a very formal piece but the idea actually came from a dream. In the

dream, somebody took me up to the cosmos into black space and showed me

opals growing in the darkness. I was being told that they have energy

and frequency. So I was quite intrigued by these stones mined from the

earth that have a measurable frequency. So even if it was a dream, it

is still quite formal, personal, yet very formal. I was also interested

in working with the relationship between the visual and the

sonic/aural/musical in this piece and exploring perceptual experiences

involved in translating internal experiences into the external to

represent different states of consciousness. Erin:

This cultural critic named Gene Youngblood wrote a book in the 70’s

called Expanded Cinema about how all of these expansive techniques in

film have been parallel with the expansion of consciousness. Dodda:

Compared to where video was in 2000, you had to have a video camera and

know how to use it, but today it’s totally part of our daily life. It’s

so interesting how video is the same material as our memory, like our

current state of consciousness. |

|

SOUND AND VISION - DON’T YOU WONDER SOMETIMES?

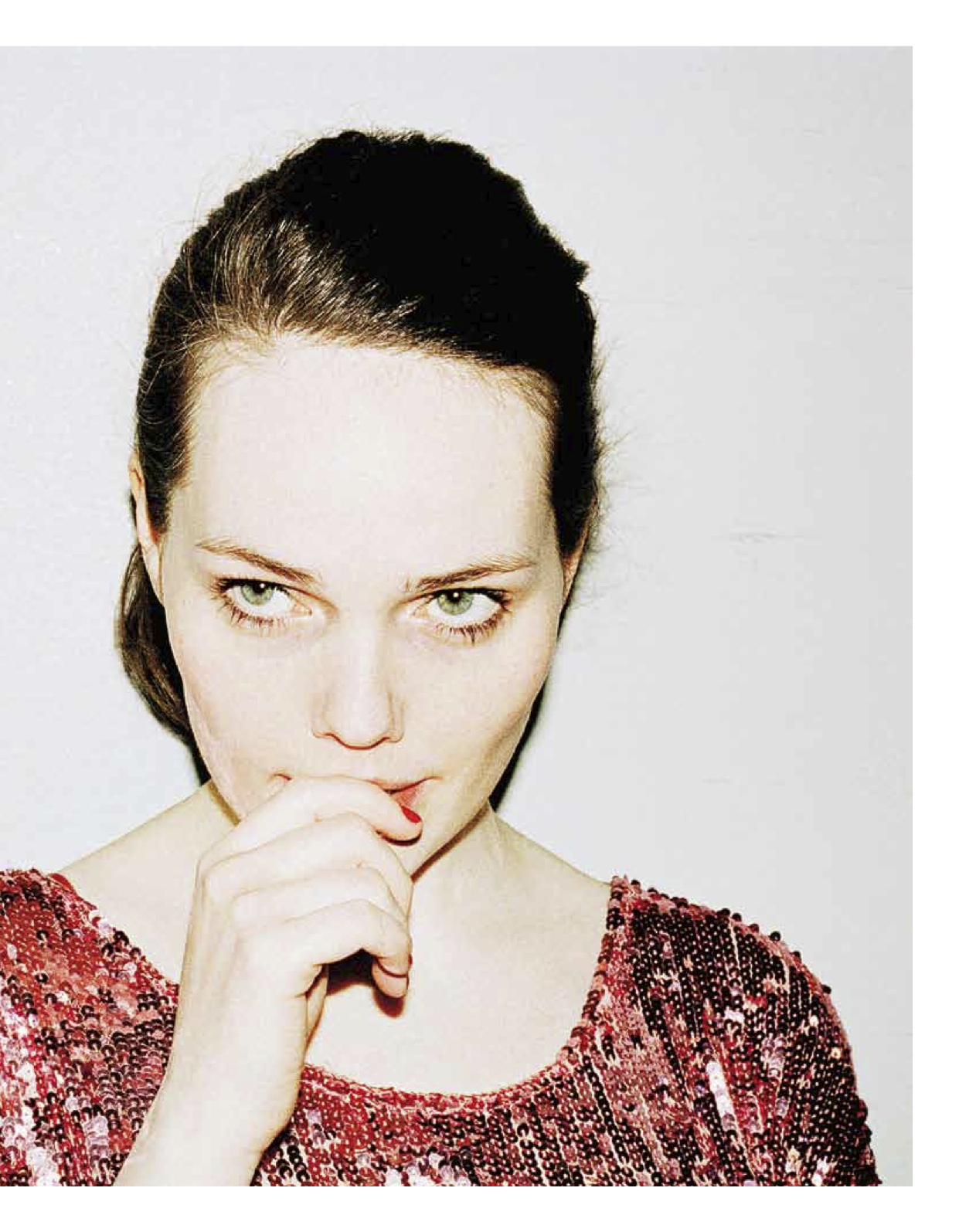

”Skal vi tage interviewet på dansk eller engelsk”? er mit første

spørgsmål til Dodda Maggý. Jeg ved ikke meget om hende, udover at hun

er født og opvokset i Island og er uddannet fra Kunstakademiet i

København. ”Lad os tage det på engelsk”, svarer hun og tilføjer, at hun

på dansk er bedre til det skrevne ord end det talte.

Det er da heller ikke talte eller skrevne ord, der præger Maggýs

kunstneriske arbejde. Hun beskæftiger sig nemlig med audiovisuelle

værker og installationer i et felt mellem kunst og musik. Stillestående

såvel som bevægelige billeder med og uden lyd, drømmende og sanselige

billedsprog, visuelle virkemidler og kompositoriske processer er

centrale omdrejningspunkter i Maggýs værker, hvilke bl.a. kan ses på

hendes hjemmeside og videotjenesten Vimeo – og i øjeblikket i ARoS’

mørke udstillingsrum.

Når billede og lyd smelter sammen ”Udgangspunktet for udstillingen har været at præsentere de mange facetter i mit arbejde. Derfor afspejler de udstillede værker på forskellig vis min praksis, der beror på at undersøge det sprog, der knytter sig til billeder og musik,” fortæller Maggý og uddyber: ”Mine performative værker belyser ofte forskellige mentale og psykologiske tilstande eller erfaringer, der f.eks. knytter sig til minder og drømme. Dem forsøger jeg at give en form, således de kan blive oplevet som levende billeder. I det formelle arbejde interesserer jeg mig for at skabe sansemæssige oplevelser, bl.a. ved at udforske de strukturer og fortællende kvaliteter, der knytter sig til video og lyd – ofte i en kombination eller sammenstilling.”

Beskueren for øje ”Jeg stiller spørgsmål uden at have svar. Derfor er beskueren vigtig for mig. Man kan sige, at mine værker afhænger af ham; hvad han føler og relaterer til, og hvordan han ønsker at ’være i’ værket,” siger Maggý og påpeger, at hendes mål med sin kunst er skabe en oplevelse. Beriget af oplevelser bliver man da også i mødet med Maggýs værker, der ikke kun beror på mystificering eller suspense, men som også påkalder sig beskuerens ubetingede opmærksomhed og tilstedeværelse i særegene universer, som man ikke kan undgå at blive fanget ind i – fysisk såvel som psykisk.

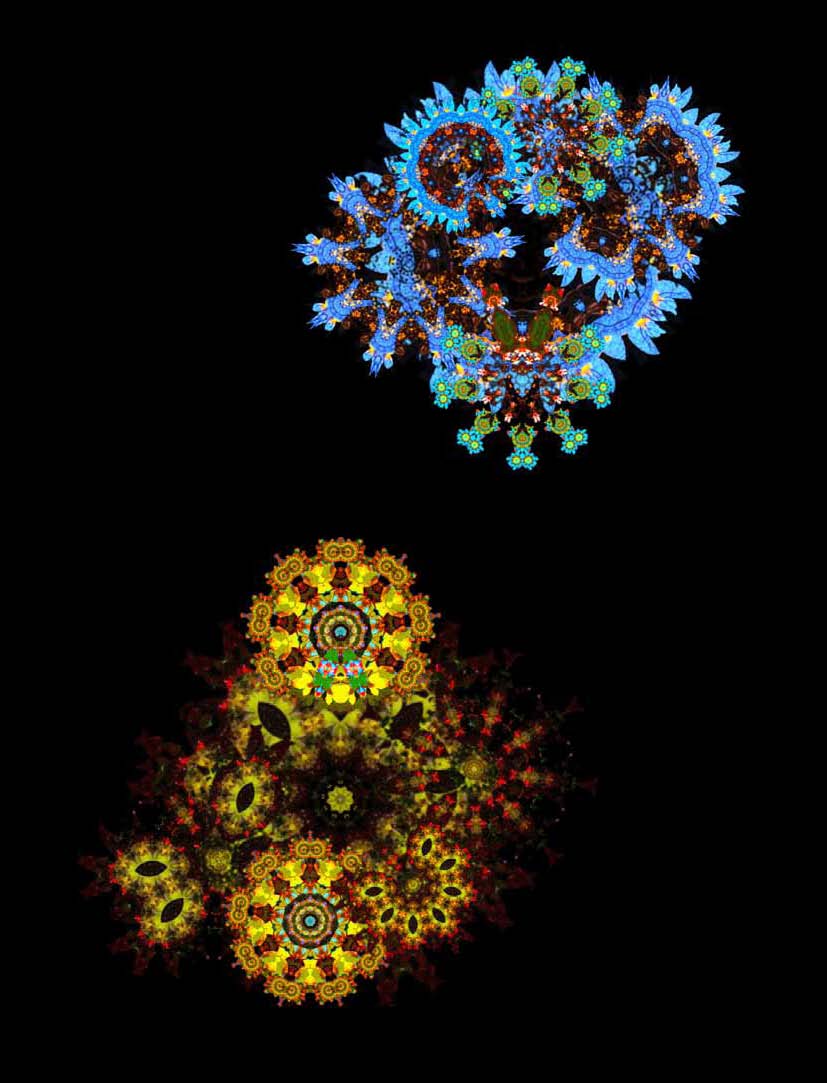

Et indre liv i mange farver ”Værket handler om mine egne oplevelser af migræneanfald, hvor jeg går rundt i blinde. Her oplever jeg neurologiske forstyrrelser, og jeg ser kun blinkende farver og former,” forklarer Maggý. ”Værket er således et eksempel på, hvordan jeg søger at materialisere indre, immaterielle oplevelser i mit arbejde.”

Om værkets tilblivelse fortæller Maggý, at hun har filmet blomstrende

planter og samplet billederne. Derefter har hun fjernet blomsterne fra

baggrunden, reorganiseret dem og skabt nye organiske former ved brug af

spejleffekter. Denne omdannelse er blevet gentaget igen og igen og på

den måde tager de levende ”blomsterbilleder” nu form som en art

hallucinationer. ”Værket er en struktureret form for visuel sammensætning, der er redigeret på samme måde, som var det en sang, hvor man tager hensyn til timing og flow,” siger Maggý og uddyber: ”Med værket ønskede jeg at skabe en energi, hvor hver ramme var i konstant bevægelse – hvor billeder skifter hvert sekund. Selvom der ingen lyd er, er den ikke på ingen måde fraværende, idet den tager musikalsk form af farve, bevægelse og rytme. På den måde kan man sige, at værket handler om at gøre lyd visuel og at få en synæstesi mellem lys, farver og lyd til at opstå.”

Når lyd bliver visuel

Hvad man som beskuer måske ikke lægger mærke til ved første øjekast er,

at lydens styrke og intensitet er bestemmende for, hvordan billedet

lyser op og toner ud i det mørklagte udstillingsrum. Maggý fortæller, at med ”Lucy” har hun arbejdet med tanken om, at stemmen er egenrådig og bruger blot kroppen som et instrument. Kendetegnende for ”Lucy” såvel udstillingens andre værker er, at de beror på en gennemarbejdet billed- og lydside, et filmisk eller teatralsk formsprog samt at de indgyder umiddelbare sanseligt øjeblikke, hvormed Maggý understreger, at hendes arbejde beror på en fænomenologisk tilgang til sin omverden – altså til en tanke om, at vores oplevelse i kraft af sansemæssige erfaringer.

Kunsten at udvide ørerne og øjnene ”Fordi jeg er en kunstner, som har en musikalsk baggrund, er det naturligt for mig at bruge musikken til at få mine idéer til at komme til udtryk. På den måde har jeg skabt mit eget kunstneriske sprog” siger Maggý og fortsætter: ”Nogle ville måske kalde det, jeg laver for musik eller lydkunst. Nogle gange synes jeg selv, at det klart defineret, andre gange falder det imellem begreber.”

Det er tydeligt, at det for Maggý ikke handler om faste begreber eller

principper. Det handler mere om at kredse om, at betone lydens

strukturelle lag og lade dens former og potentialer som materiale og

betydningsskaber komme til udtryk. ”Som komponist har jeg altid været fascineret af at udforske lyde og åbne op for idéer om, hvad musik kan være, hvorfor den kan få os til at blive følelsesmæssigt overvældet og give os fornemmelser af at være i en anden tid eller på et andet sted end vi faktisk er,” siger Maggý og forklarer, at hun er interesseret i at materialisere lyd ved at udforske, hvordan den bliver til og kan fremtræde foruden udforske, hvordan musik kan blive oversat til samme visuelle kvaliteter, som bevægelige billeder har.

”Man kan sige, at jeg gerne vil udvide ørerne og øjnene lidt” siger hun og smiler.

Processuelle rejser

”Det hele starter med en idé eller følelse, som kan være visuel eller

auditiv. Den forsøger jeg så at materialisere ved at gøre den til en

struktur eller form, der opstår eller udvikler sig i selve processen.

På den måde kan jeg nogle gange føle mig som en videnskabsmand eller en

opfinder i laboratoriet,” siger Maggý og forklarer, at hun hele tiden

udvider sine arbejdsmetoder for bedre at kunne skabe, hvad hun kalder

for sine ”lyriske universer”, som er meget personlige. Blandt andet

arbejder hun med en animationsteknik, som hun selv har udviklet, og som

kun hun kan bruge. ”Mine videoer er ret ’håndlavede’, selvom jeg arbejder ved en computer. Mange tror fejlagtigt, at videoerne er computergenererede. Det er faktisk animationer, der tager måneder at lave.” Det er også en af grundene til, at Maggý foretrækker at arbejde i sit studie. Hendes arbejdsprocesser strækker sig over lang tid, og det er ikke usædvanligt, at nogle værker tager op til et år at lave – måske endda længere. Derfor arbejder hun også med flere værker på samme tid. Det giver en god variation, samtidig med, at det også kan berige processerne. Det er et langsommeligt arbejde, men altid spændende, da det også bringer overraskelser: ”Når man arbejder længe med et værk, hvor man er fokuseret på de mindste detaljer, fjerner man ofte fokus fra helheden. Derfor kan man også pludselig opleve eller se en effekt i sit arbejde, som man ikke havde forudset. På den måde er det en rejse – fra idé til det endelige værk.”

Teknologiens indflydelse ”For mig handler om at være nytænkende

og om at tænke over, hvordan man præsenterer noget visuelt for

beskueren, som er andet og mere end blot mere information. Dét, jeg

gerne vil er at skabe et rum – en pause fra omverdenen – hvor vi kan

opleve og reflektere på egen hånd.” Dodda Maggý er født i 1981. Hun har

uddannet sig inden for musik og kunst og har studeret på The Iceland

Academy of the Arts og Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi. Siden midten

af 00’erne har Maggý været aktiv på den internationale lyd- og

kunstscene og har med sine værker bidraget til udstillinger, events,

messer og festivaller. I dag bor og arbejder hun i Reykjavik. I marts 2015 slog ARoS dørene op for en

ny udstillingsrække ved navn ARoS FOCUS//NEW NORDIC. Fokus blev rettet

mod den nordiske samtidskunst og havde som udgangspunkt at vise en

række yngre nordiske kunstnere med meget forskelligartede produktioner.

Dodda Maggý er den niende og sidste kunstner i udstillingsrækken. Hun

modtager i den forbindelse legatet Young Talent, som gives med støtte

fra Det Obelske Familiefond. |

www.corridor8.co.uk

|

|

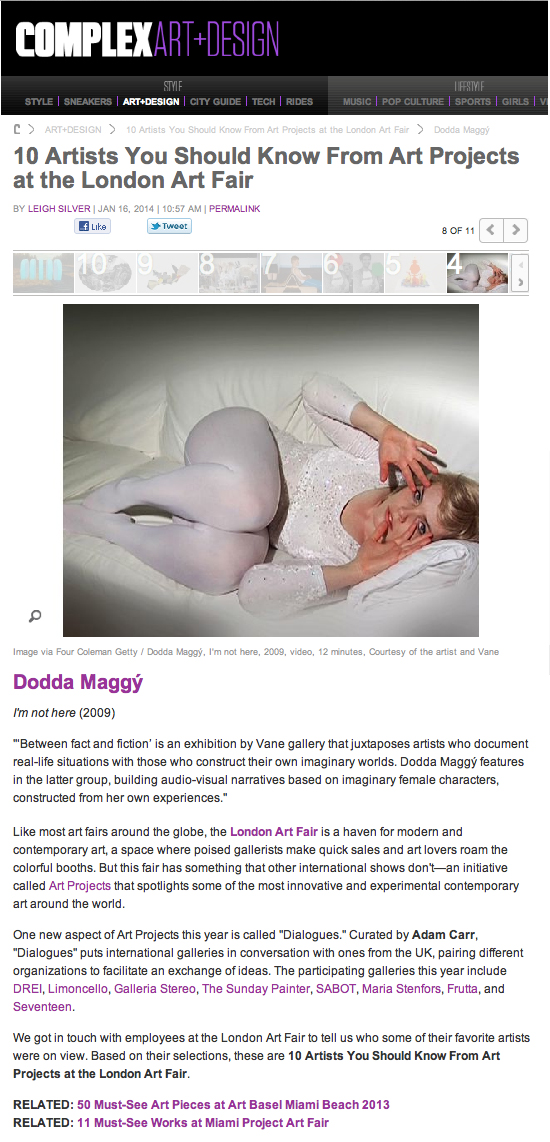

www.complex.com/art-design/2014/01/london-art-fair/maggy |

| 20 March 2013 Interview in the HuffPost Arts & Culture with Tanya Toft co-curator of Nordic Outbreak 'Nordic Outbreak': Curator Tanya Toft On How Nordic Art Extends Far Beyond Bjork  What do you

know about Nordic art? If your knowledge begins and ends with Bjork we

suggest checking out "Nordic Outbreak," an

exhibition illuminating the

Northern region's influences and aesthetics. The Streaming Museum

exhibition features over 30 moving image works from Nordic artists that

will be projected on screens in public spaces

throughout New York City - including a "Midnight Moment" with Bjork in

Times Square. Many of the works on display that

were selected by co-curators Nina Colosi and Tanya Toft respond to

the clashing identities in our new digital age. We reached out to Toft

to learn more.

www.huffingtonpost.comHP: The press release for the show mentions the stereotypical Nordic aesthetic as "minimal, melancholic and naturalist"... something this exhibition aims to change. Which artists were influential in casting Nordic art this way? TT: An artist like Olafur Eliasson is a contemporary Nordic artist whose work with light, space, fog and sensitive play with colors of nature’s elements, reveal an aura of something Nordic. It conveys certain aesthetic ideas that reveal symptoms of romanticism and a seeking after the sublime rather than the beautiful. There is a melancholic feel to that meeting between man and nature, which we also find in the works of Jesper Just for example, who is in the Nordic Outbreak program with his work “Llano” (2012). In selecting the works for Nordic Outbreak, we were also interested in renegotiations of nature and landscape, which artists like Dodda Maggy, QNQ/AUJIK, Jette Ellgaard and Magnus Sigurdarson enact. HP: Do you think there is a more accurate driving aesthetic of Nordic culture today? If so, what is it? TT: I don’t think there is one driving aesthetic, but the artworks in Nordic Oubreak show symptoms of improvisation and play, which is somewhat “new” in a Nordic art context that might have been characterized more by control and high quality. Some of the artworks express aesthetic cultures that were not “born” out of a Nordic context. There is a struggle between introspection and extroversion – following a right wing and nationalist political period in some of Nordic countries up through the 2000s, financial crisis, and in response to the digital age. There seems to be a clash between looking in and looking out, guarding and departing. In quite a few of these works, existential questions are brought beyond the invidividual and psyche – which has been a tendency, perhaps – and pointed toward one’s role in a greater context. It is also characteristic that these artists express and awareness of the medium they are working with, and in many of the works the audience is addressed as individual viewers whose optics are shaped in a contemporary world. That we find in the works by for example Marit Følstad, Mogens Jacobsen, and Iselin Linstad Hauge. HP: What was one of the greatest challenges of putting the exhibition together? TT: Asking questions like: What does it mean to take ‘the digital’ as a curatorial premise - and wrapping your head and decisions around that. I don’t think there is one model. We wanted to instigate logic to the exhibition that would open up for questions concerning materiality, originality, network, and questions relating to the role of moving image in an urban context. Also, working around the partnerships we established along the way has been an interesting challenge - conceptually and practically. We lost some venues in New York that were ruined by Hurricane Sandy, which was challenging but which eventually let to exciting partnerships that we had not anticipated, for example with Dumbo Improvement District and the Manhattan Bridge Archway. HP: What is the age range of the 30 artists represented? Were you specifically looking for a selection of younger artists? TT: Age was not a parameter. In fact, quite a few of the artists are quite well established. We were looking for artists that experiment with moving image, as a medium and thematic frame of expression. This is why the collection includes very ambitious animation works as well as classic, documentary-style video works. The show is not just about “new” aesthetics - it is very much about the issues put forward as societal critiques, as voices of “the happiest people” that are rarely expressed in an international context. HP: For those of us who are huge Bjork fans, which artist do you think is following in her footsteps? TT: I think there is a tendency of artists to become accepted for their multimedia talents, of which Bjork is a pioneering example. We selected her for the Midnight Moment in Times Square because she is a performance and visual artist who completely brakes with the barriers of art, technology, music and digital structure, which she demonstrated with her Biophilia album. There is no “next Bjork”. But there is a generation of young artists who cross over music and media art (e.g. Oh Land and Lucy Love, to name a few from the Danish music scene), not just by hiring good stage designers but by expressing their music visually as well. That is really interesting - a new kid in the school of fine art, I am sure. www.nordicoutbreak.streamingmuseum.org |

|

The Music of Vision

ARTnord Magazine no. 11

Paris, May 2012 By Rune Søchting Sound and music are the departure points in the work of Icelandic artist Dodda Maggý (b. 1981). Besides creating installations, she veers towards video as the medium for her work. A recurrent theme in her works is the gaze and the act of seeing. The theme is brought to presence by a staging of characters who are almost always named. Female names entitle many of her works. The works often establish a charged interplay between the gaze of the character and the audience, where the character is the object under the gaze of the audience. It is also the case in the video DE-CORE (Aurae), where vision is the central motif, albeit in a more abstract way. The silent video-projection DE-CORE is an animation of symmetric compositions that unfold to reveal an extraordinarily complex living and organic structure composed of constantly changing small mobile elements. From a purely stylistic point of view, we are reminded of the “visual music” tradition originating in experimental films and animation. However, as we will see, it is more a case of a mise-en-scene of the “music of vision.” The concept of a visual music figures frequently in the history of art. The idea of a “visible” music usually takes the form of a sound-image that visually reflects features that we associate with sound or music. Take the symmetrical patterns of grains of sand from Chladni’s experiments, Klee’s movement schemas or Kandinsky’s experiments with sound-color relations. The introduction, in the twentieth century, of different image-producing technologies, such as color-organs and color projections, created new possibilities for the concept of a sound-image as a dynamic phenomenon. A moving sound-image can be found in the films of many artists such as James and John Whitney, Mary Ellen Bute, Len Lye and above all Oskar Fischinger (who has also experimented with optic sounds, the transformation of graphic forms into sound). Under the idea of a visual music an extraordinary series of works were developed involving animation of light and colors in relation to music. With the arrival of the digital image, new experimental possibilities in translating sound forms into visual forms occurred, leading to the presence of color “visualizers” in multimedia players, among others. The animation presented in DE-CORE shares common features with these historical examples of visual music. Although music as an audible element is absent, the animated, dynamic forms presented in the work, invite a “musical” reading of the visual pattern with its prominent pulse and rhythm. The pattern’s various concentric circles give a graphic impression of harmonic and structural relations. Nonetheless, the work’s main emphasis is on the visual, with its established dynamic interplay between parts and the whole as a key element. The emerging animated pattern appears as an ever-changing complex graphical perpetual mobile. The image’s global composition is organized around a fixed center with multiple, crossing lines of reflection, much like a kaleidoscope, but with more dynamic. The overall pattern emerges and is changed by the movement and change in the individual small elements. The movement of these multiple particles attracts one’s attention and makes it difficult to focus on the macro-level of the image. At the same time, numerous reflections prevent one from maintaining attention on specific details. Attention is once again drawn towards the global form. Visual attention fluctuates between these levels without finding a state of rest or resolution. There is something undeniably baroque in this fractal principle of pattern formation. The visual particle-elements in the pattern are all extracted from hundreds of video recordings of flowers. Each of them were individually processed, isolated and transformed through a special mirroring process. The resulting, more or less abstract forms were then reflected again and animated in order to create the elementary level of the image, in which the original flower images tend to disappear. Dodda Maggý acknowledges the parallel that exists between the minute animation work with video recordings and her musical work with sound recordings. In this approach one finds an echo of the idea of a music composed from recorded sounds, as conceived by the French composer and radio technician Pierre Schaeffer in the 1950s -1960s. Schaeffer imagined a new music that could, in principle, contain all types of sounds, not limited to the timbre of instruments in a traditional orchestra. As an analogy, it is tempting to think of DE-CORE as a kind of concrete visual music. Like the recording of sounds in concrete music, the recognizable flower-images in the video-recordings is transformed. What remains is a video material that is detached from reality. In DE-CORE, the question of the status of the “musical” is submitted to yet another alteration, as suggested by the parenthesis (Aurae) in the title. Aurae refers to a pathological state that appears just before a migraine attack, in which flickering perturbs vision. This reference opens for a possible interpretation of the visual pattern as a visible music, which at the same time disturbs our vision of reality. Following this line of thought, the visual music presented in DE-CORE is not something that appears when one sees the world in a certain way⎯which according to Schaeffer was a condition for the perception of the concrete music in everyday sounds⎯but something that comes from an interior vision. In this case, what is “musical” would be something inherent to sight. The work thus moves the idea of the music of reality to the eye itself, and makes it part of the logic of vision. Thus it is no longer the music of the visual that is thematized in the work, but rather a music specific to vision. Thus DE-CORE suggests a possible difference between music of the visible and music of vision. Rune Søchting, an artist, works on his doctoral thesis at the Royal Academy of Arts in Denmark. From 2007 to 2009, he was the coordinator of the study program Nordic Sound Art. |

|

Visuellt om och med ljud

Sydsvenskan Review on Horizonic in Ystads Art Museum Sweden, 28 September 2012 By Carolina Söderholm ”Horizonic – unfolding space through sound art”. Efter ett missförstått konstprojekt sparkades han från lärartjänsten på Århus konservatorium, dömdes för stöld och fick passet konfiskerat. Men den färöiske kompositören Goodiepal lät sig inte begränsas av det. Istället cyklade han från Köpenhamn till Moskva och sprider numera sin radikala datormusik via nätet och föreläsningar, som gränsar till performanceverk. Nu står hans hembyggda liggcykel, i vilken han vanligen arbetar, sover och genererar ström till sin dator med, parkerad på Ystads konstmuseum. Fast jag saknar möjligheten att lyssna på hans musik. Istället presenterar han sitt arbete och liv som kulturell hacker med anarkistiska skriftrullar och personliga ägodelar. Om Goodiepals bidrag är det mest galna och roliga, rymmer vandringsutställningen ”Horizonic” en rad verk tillkomna under rätt extrema förhållanden. Temat är smalt, men fungerar genom sin tydliga profilering: konst som på olika sätt förhåller sig till ljud samt till det nordligaste Norden. Alla tio konstnärer har någon anknytning till Färöarna, Svalbard, Nordnorge, Island eller Grönland. Så blir också naturen, med sin stränga kyla, istäckta vidder och kärva förutsättningar, en utgångspunkt för flertalet konstnärer. Grönländska Jessie Kleemann och Iben Mondrup iscensätter en schamanistisk performance i vattenbrynet där rytm och kropp, nutid och urtid smälter samman. Avsevärt mer intressant, med oroande politisk kraft, är svenska Åsa Stjernas bidrag. I samarbete med forskare vid Internationella Meteorologiska institutet vid Stockholms universitet har hon skapat ett ljudverk som i realtid baserar sig på mätningar av hur Nordpolens is smälter. En klirrande, gnistrande, dovt pulserande upplevelse av den globala uppvärmningens konsekvenser. Allt på utställningen är nu inte natur – eller ljud – vilket bidrar till helhetens styrka. Ljudkonst, som lagom till hundraårsjubileet av pionjären John Cages födelse uppmärksammas med satsningar i både Stockholm och Köpenhamn, kan annars ibland bli en rätt torftig visuell historia. Men här agerar bland andra isländska Dodda Maggý motvikt, med sin ljudlösa, psykedeliska videoprojektion baserad på kalejdoskopiska speglingar av blomsternärbilder. Genom mönstrets växlingar, transformationer och glimrande explosioner förmedlar hon känslan av att se ljud, istället för att höra det. Ett av de mer spännande verken på ”Horizonic”, som lyckas ganska bra med konststycket att vara en visuell utställning – med och om ljud. Ystads konstmuseum i samarbete med tidskriften ARTnord, t o m 21.10. |

|

Andinn í lampanum Morgunblaðið Review on Lucy in Reykjavik Art Museum Reykjavik, 7. February 2010 Anna Jóa Listasafn Reykjavíkur kynnir unga listamenn í D-sal Hafnarhússins; að þessu sinni sýnir þar Dodda Maggý. Um er að ræða innsetninguna Lucy sem byggist á hljóði og myndbandi. Með tæknina að vopni skapar listamaðurinn skilyrði fyrir óvenjulega skynræna upplifun sýningargesta. Fyrst er skynjunin rugluð eða „afstillt“ með því að leiða gesti inn í myrkvað rými þar sem ómar angurvær söngur. Hljóðið ferðast um salinn og er þannig skerpt á skilningarvitunum, ekki síst heyrninni þegar „áhorfandinn“ reynir að átta sig á aðstæðum. Og áhorfið fær sinn skammt; athyglin beinist fljótlega að skjámynd sem í tilviki undirritaðrar virkaði í fyrstu sem afstrakt litaflæmi, og stemningin fljótandi, óhlutbundin og andleg. Þá tekur á skjánum að glitta í konu í skrautlegum búningi, sem leiðir hugann að sirkus eða skemmtanaiðnaði af einhverju tagi. Fyrir utan að vera blekking á tjaldi, býr þessi kona yfir talsverðum annarleika; látbragð hennar er tregafullt og hún sést aðeins að hluta sem flöktandi ímynd í myrkrinu, dálítið eins og logi sem leitast við að draga í sig súrefni – en hér er það hljóðið, söngurinn, sem glæðir ásýnd verunnar. Við rétt ákall birtist hún eins og andinn í ævintýrinu um Aladdín. Dodda Maggý líkir hér á vissan hátt eftir bíóreynslunni, þ.e. þeirri sem fæst í dimmum sýningarsölum kvikmyndahúsa. Hún einangrar þó „bíógestinn“, magnar og kemur óvanalegri hreyfingu á hljóðið, einfaldar og dempar myndina. Ólíkt því sem gjarnan gerist í bíó – að áhorfandinn gleymi sér í sjónarspilinu – virkjar eða lýsir Lucy smám saman líkamlega skynjun og tilfinningu fyrir rýmislegri stöðu sýningargesta sem umluktir eru ljósgeislum og ósýnilegum hljóðbylgjum. Hér er á ferðinni fallega unnin sýning sem kveikir ýmsar hugleiðingar um samspil skynjunar og tækni, efnis og anda. Lucy í D sal Listasafn Reykjavíkur, Hafnarhús 15. janúar - 21. febrúar 2010 Sýningarstjóri: Yean Fee Quay |

|

EXIT09

From the Catalog for the Graduation Exhibition from the Danish Royal Academy of Fine Arts

Stine HebertCopenhagen, 1 May - 20 June 2009

The experience of fainting, waking up and realizing that one has been

in a parallel state has influenced Dodda Maggý’s artistic practice. As

a child she often fainted, and it became an occurrence to be caught

between different states of consciousness. The unbound connection

between the physical residence of the body and the mental universe of

the psyche has created an interest for the increased receptiveness and

emotional experiences of the situation.